Pouchitis: Practical Points for Pathologists

Paula Borralho Nunes, H-ECCO Member

Paula Borralho Nunes © ECCO |

A significant number of patients with Ulcerative Colitis (UC) will require a colectomy [1], with the most frequent indications including medical refractory disease and the occurrence of dysplasia or cancer in cases of longstanding disease. A total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) has become the surgery of choice for the “definitive” management of UC since it avoids a permanent stoma while removing all diseased colonic mucosa [2], but it is also used for familial adenomatous polyposis and sometimes (advertently or inadvertently) for Crohn’s Disease (CD). However, although this surgery has significantly improved the quality of life of patients with UC, complications such as fistulas, abscesses, strictures of the anastomosis and pouchitis can occur after restorative proctocolectomies. Pouchitis refers to a chronic relapsing inflammatory condition with active inflammation of IPAA mucosa and is considered to be a primary “non-specific, idiopathic inflammation of the neorectal ileal mucosa”.

Pouchitis is the most common long-term complication of ileal pouch surgery (affecting up to 60% of patients) and has a significant adverse impact on the patient’s quality of life. Signs and symptoms of pouchitis can include diarrhoea, abdominal pain, joint pain, cramps, fever, an increased number of bowel movements, night-time faecal seepage, faecal incontinence and a strong urge to have a bowel movement.

The aetiology of pouchitis is not entirely understood. Bacterial overgrowth, altered balance of luminal bacteria, mucosal ischaemia, nutritional deficiencies, lack of short chain fatty acids and faecal bile acid toxicity have all been suggested as possible aetiological factors [3].

Diagnosis of pouchitis based on symptoms alone has been shown to be non-specific since symptoms can originate from a myriad of aetiologies, not necessarily inflammatory in nature. As a result, the diagnosis of pouchitis should generally be based on presence of the appropriate constellation of symptoms, combined with endoscopic and histological assessment [4]. There is in fact a good correlation between more severe grades of histological inflammation, frequency of defaecation and endoscopic appearance.

Histopathology of pouchitis

According to ECCO-ESP Histopathology Consensus statement 21: “For a proper histologic evaluation of pouchitis multiple biopsies are recommended. The exact location has not been determined but according to some data it is useful to take biopsies from the anterior and posterior wall avoiding suture lines. Samples from the posterior wall are more likely to show the inflammatory changes” [5].

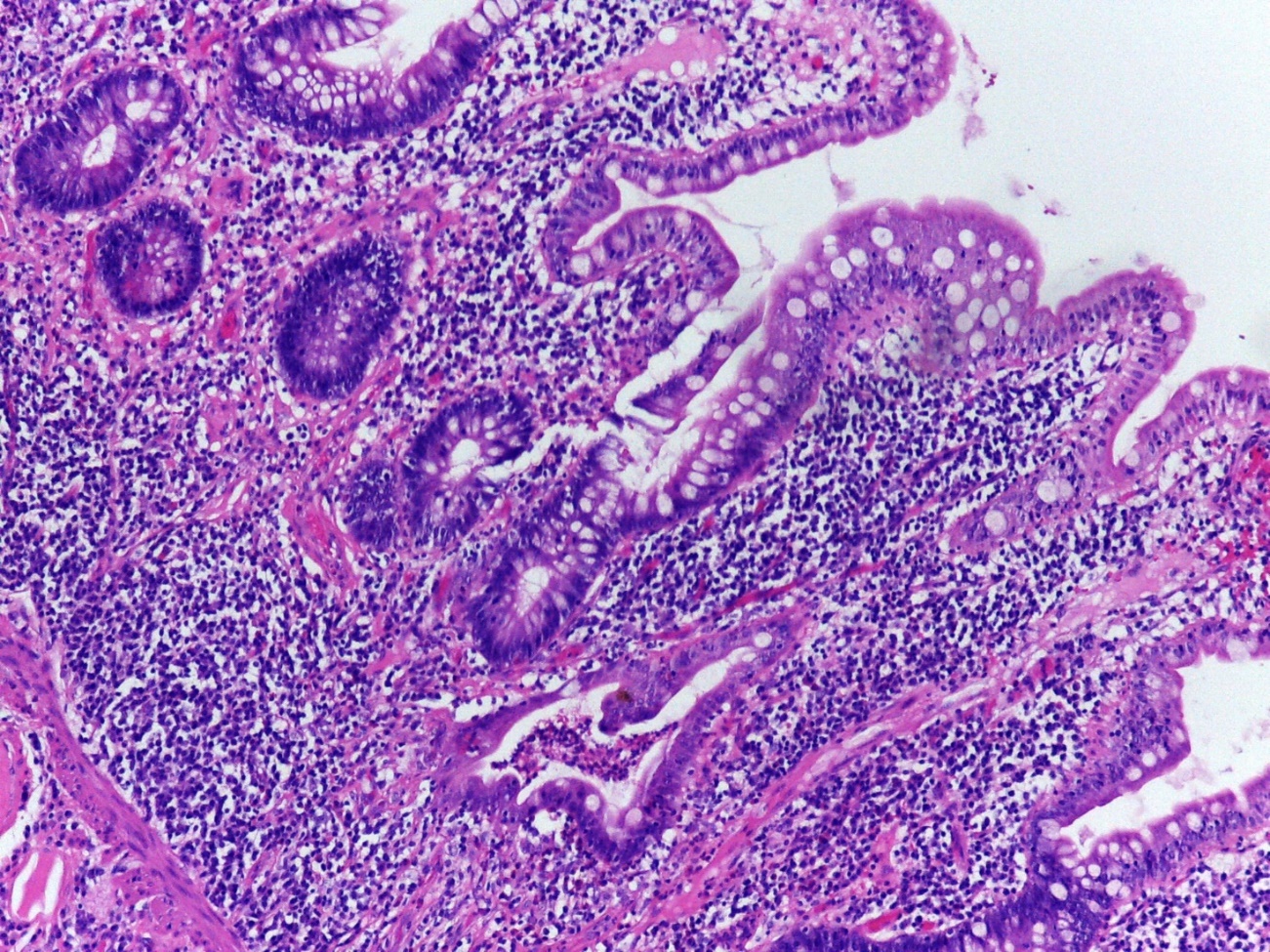

Biopsies from pouches are best reported descriptively regarding quantity of acute and chronic inflammation, the presence of crypt abscesses, erosions and ulcers, and also loss of villous height, presence of pseudopyloric metaplasia, granulomas and presence of dysplasia (Figure 1). From a histological point of view, pouchitis is a gradable phenomenon, based on extent of active crypt injury.

Various scoring systems have been developed to standardise the diagnosis and assessment of the severity of pouchitis. The Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI) quantitates clinical symptoms and endoscopic and histological features (acute histological inflammation: crypt abscess and ulceration) on three separate six-point scores, whereby a total score higher than 7 is indicative of pouchitis [6]. The Heidelberg Pouchitis Activity Score (PAS) also includes the histological features of chronic inflammation and distinguishes between three grades of pouch inflammation (mild adaptive inflammation, moderate pouchitis and severe pouchitis). Scores greater than 13 are considered to be pouchitis [7].

Most pouches have some degree of inflammation, which can be patchy or diffuse. However, chronic inflammatory changes should be distinguished from true pouchitis [8]. In fact, mucosal architecture distortion, villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia and infiltration of the lamina propria by mononuclear cells, eosinophils and histiocytes can be seen in biopsies from “healthy” pouches and are considered adaptive changes. As “colonic metaplasia” occurs more frequently in patients with pouchitis, it has been suggested that it may be a “reparative” rather than an “adaptive” response.

Besides adaptive changes, mild ischaemic changes can be observed in a few patients, while others may show features of mucosal prolapse, such as fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria and a disrupted muscularis mucosae. Deep lymphoid follicles can also be seen in excised pouches and should not refute a diagnosis of UC. In fact, diagnosis of CD should only be made when re-examination of the original proctocolectomy specimens shows typical pathological features of CD [9].

Pouchitis should be distinguished from “cuffitis”, i.e. inflammation in the columnar cuff mucosa distal to the pouch, or islands of columnar mucosa that may be left behind. CD10 staining (expressed in ileal samples) or tropomyosin isoform 5 (hTM5) (not expressed in genuine ileal samples) may confirm the biopsy site.

Finally, histological assessment should also help to rule out opportunistic infections (cytomegalovirus) [10] and dysplastic changes.

In conclusion, assessment of mucosa from IPAA for UC can be a valuable tool when diagnosing pouchitis, but pathologists must be familiar with the concept of adaptive changes, be aware that activity of inflammation needs to be categorised and avoid misinterpretation of deep lymphoid follicles as synonymous with CD.

Figure 1: Mucosal architecture distortion, villous atrophy, cryptitis and crypt abscesses in an ileal pouch biopsy. © Paula Borralho Nunes |

References

- Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Colorectal cancer risk and mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1444–51.

- Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, et al. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120–7.

- Mahadevan U, Sandborn WJ. Diagnosis and management of pouchitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(6):1636–50.

- Shen B, Achkar J-P, Lashner BA, et al. Endoscopic and histologic evaluations together with symptom assessment are required to diagnose pouchitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:261–7.

- Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A, et al.; European Society of Pathology (ESP); European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:827–51.

- Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409–15.

- Shen B, Achkar JP, Connor JT, et al. Modified pouchitis disease activity index: a simplified approach to the diagnosis of pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:748–53.

- Warren BF, Shepherd NA, Bartolo DCC, Bradfield JWB. Pathology of the defunctioned rectum in ulcerative-colitis. Gut. 1993;34:514–6.

- Goldstein NS, Sanford WW, Bodzin JH. Crohn's-like complications in patients with ulcerative colitis after total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1343–53.

- Navaneethan U, Shen B. Secondary pouchitis: those with identifiable etiopathogenetic or triggering factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:51–64.