Diet in the Treatment Paradigm of Crohn’s Disease: New Evidence, New Strategies

© Nestlé Health Science |

Introduction

Franck Carbonnel - University Hospital of Kremlin Bicȇtre, France

There is an established association between a Western diet and the risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, including Crohn’s Disease (CD). Enteral nutrition has often been used to treat CD in children and adults. What evidence is there that a controlled diet can help to improve outcomes for CD patients?

From Evidence to Clinical Strategies with CDED

Arie Levine - Wolfson Medical Center, Israel

There is evidence that clinical strategies for CD can make use of dietary therapy, particularly a Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED).

Short-term therapeutic goals in CD are: clinical remission, decrease in inflammation and maintenance of remission and growth. Long-term therapeutic goals are: mucosal healing, prevention of complications and reduction in surgery, as well as doing no harm.

For a significant number of patients, diet appears to be a key driver of inflammation. The disease will only be controlled if this environmental cause is addressed.

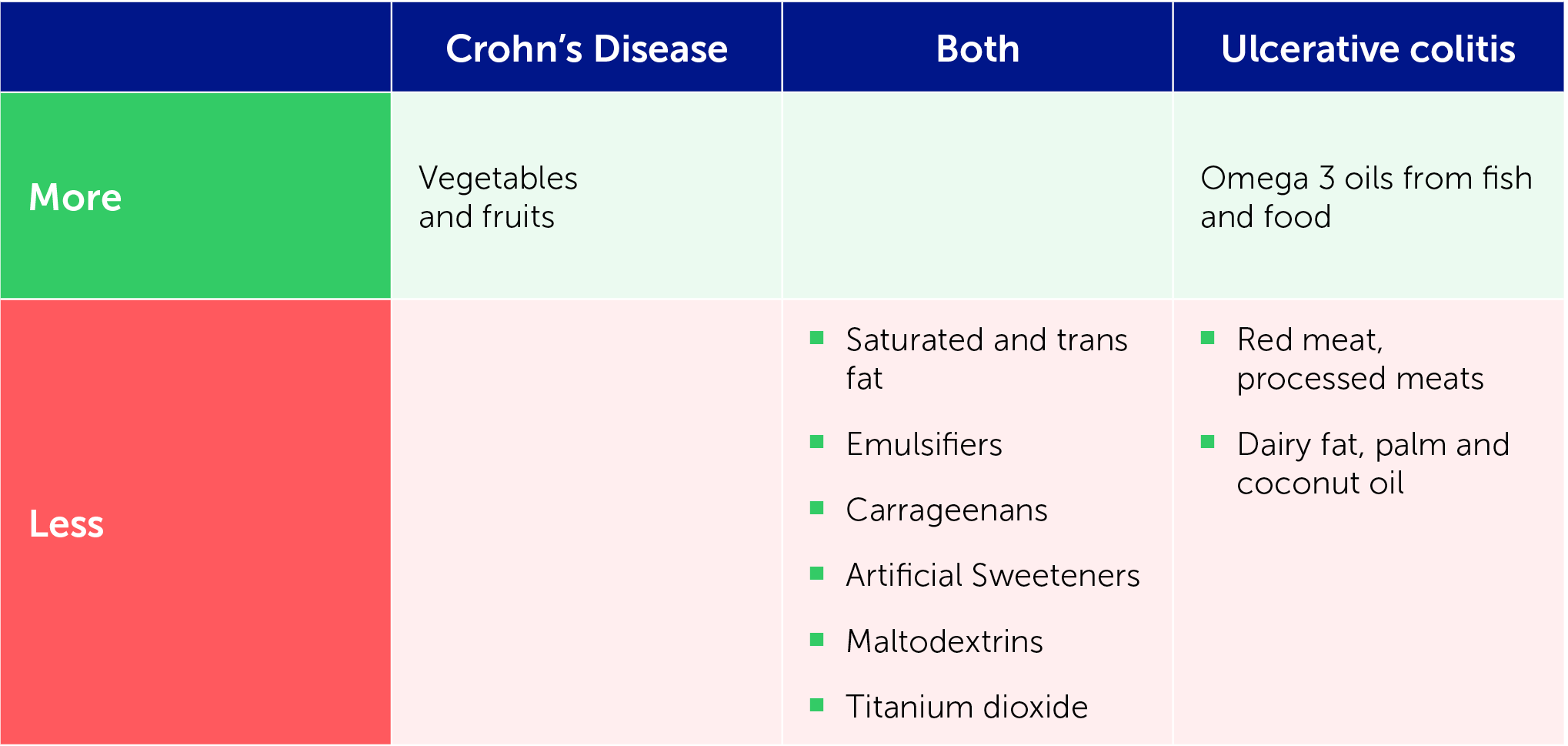

IOIBD recommendations for treatment of CD and Ulcerative Colitis are:

Are emulsifieres a problem for CD?

Emulsifiers have been posited as contributing to CD, through either the microbiome or bacterial clearance mechanisms.

A study by Sandall et al. [1] found that the most frequent exposure to emulsifiers in the British diet is from breads and baked goods as well as confectionery, chocolate, preserves, pastes and spreads. This study and two further recent studies demonstrate that emulsifiers, carrageenans and gums may have a toxic effect on the microbiome, leading to increased inflammation [1–3]. Two of the studies found soy lecithin to have no effect on the microbiome, while the third found a toxic effect only at a higher dose. This is fortunate, as soy lecithin is commonly used in medical formulas for enteral nutrition.

Evidence suggests that inulin may be pro-inflammatory and pectins may be anti-inflammatory fibres, while cellulose may be neutral when given at times of inflammation.

Identifying a dietary-responsive phenotype of CD

A dietary-responsive phenotype of CD needs to be identified in order to develop improved strategies for CD. Multiple studies [4–6] have now shown that a habitual or free diet can trigger inflammation in CD.

Dietary studies have shown that reintroduction of food after exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) leads to a rapid rise in calprotectin and a loss of response. This is not seen with CDED + partial enteral nutrition (PEN).

A paediatric CDED trial [4] compared outcomes with CDED [a whole-food diet coupled with partial enteral nutrition (PEN)] and with EEN. In the first six weeks, over 80% of patients in both arms showed response. At week 6 there was no significant difference, but by week 12, 65% of the CDED group were in sustained remission compared to 38.2% of the EEN group. Both groups showed a reduction in actinobacteria and proteobacteria in the first six weeks and an increase in Firmicutes. However, across weeks 0–12, the CDED group showed a sustained decrease in proteobacteria whereas the EEN group experienced a major rebound in dysbiosis to pre-treatment levels as well as a rise in calprotectin after re-exposure to food despite using the same amount of PEN.

These results suggest that food may be a major driver of the dysbiosis of the microbiome involved in CD, and that diet could be crucial in developing a therapeutic strategy to treat and prevent recurrence of CD.

What is CDED?

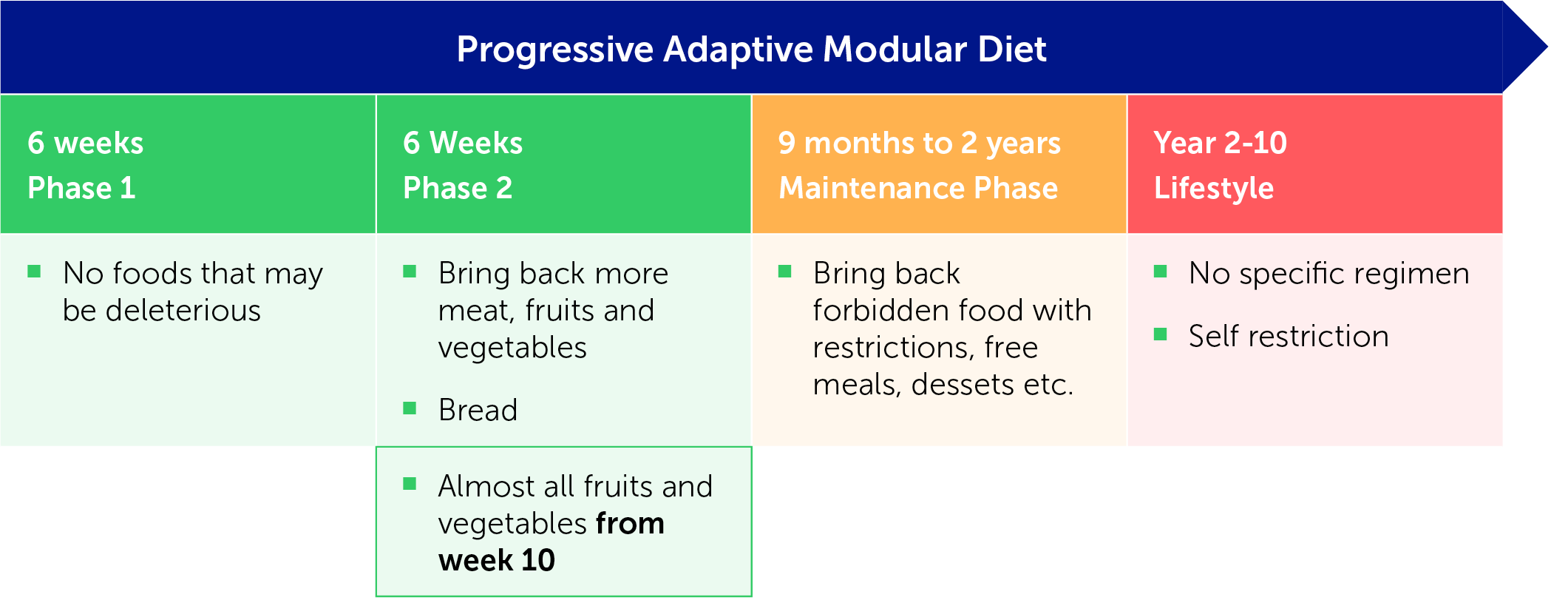

CDED is a progressive adaptable modular diet including three phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The three phases of the CDED

Identifying dietary-responsive disease

Dietary therapy involving change in the diet (either CDED or EEN) as the only intervention results in a rapid response within 3 weeks. This means the use of CDED or EEN can identify dietary-responsive disease.

A study by our group [7] found that 75% of patients went into remission within three weeks on either diet; over 60% remained in remission at week 3 and over 40% of patients with elevated CRP had normalised within three weeks.

Treatment

CDED is the first dietary treatment that meets all the goals of medical therapy (induction, maintenance of remission, a decrease in inflammation and mucosal healing) and is a viable strategy for patients with CD.

Choice of treatment is usually driven by four key factors:

- Disease severity

- Complicated phenotype (stricture, perianal fistula, penetrating disease)

- Extraintestinal disease (arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum)

- Physician preference – biologics for all vs accelerated step up

When diagnosing CD, physicians should identify whether the disease has a dietary-responsive phenotype, just as they should identify a complicated phenotype.

New dietary strategies with dietary-responsive CDED + PEN in children

In our practice, children with uncomplicated, mild to moderate disease who are willing to alter their diet start CDED + PEN to determine whether the disease is dietary responsive [8]. If this is the case, there are three possible therapeutic strategies:

- Drug-free strategy: CDED monotherapy then CDED maintenance if the response and adherence are good

- Reduce drug strategy: Drug combined with diet in the form of CDED, then CDED for drug de-escalation after 1 year if mucosal healing has been achieved

- Rescue: Medical therapy then CDED rescue therapy for loss of response

Strategy for complicated CD with CDED + PEN

For those with complicated mild to moderate disease requiring a biologic, a reduction in dietary exposure strategy may be tried: start with CDED + PEN phase 1 for those with new-onset disease to identify dietary-responsive disease; otherwise add CDED phase 3 to the drug as a reduction in exposure strategy.

After this, patients may either [8] follow a drug reduction strategy using drug plus CDED combination therapy then CDED for drug de-escalation, or a rescue strategy of medical therapy with CDED rescue therapy for loss of response.

Conclusions

CDED is an effective treatment for achieving remission in children and adults with CD. It can induce and maintain remission in >50% of patients and is associated with a decline in calprotectin as well as CRP and with mucosal healing.

Dietary therapy can be used to detect dietary-responsive phenotypes at diagnosis. This may help to clarify whether a drug or diet is responsible for remission.

Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet in Adults – an Addition to the Therapeutic Toolbox

Nitsan Maharshak, Tel Aviv Medical Center and Tel Aviv University, Israel

A Western diet is a known trigger for CD, increasing proteobacteria dysbiosis, intestinal permeability, inflammation and active disease. CDED + PEN involves removal of trigger foods, including animal fat, wheat, dairy, red meat, emulsifiers, maltodextrin and carrageenan from the diet, and encouraging consumption of more fruit and vegetables.

CDED + PEN has been found to be better tolerated than EEN [4]. Both diets are effective at achieving remission at week 6, but CDED + PEN is superior in sustaining remission and reducing inflammation at week 12. CDED + PEN is associated with reduction in proteobacteria and intestinal permeability.

CDED + PEN is effective in children and may be a useful salvage [9] regimen for children and young adults failing biological therapy. It also seems to be more effective in milder disease and in patients with small intestine involvement.

Open research questions include whether CDED + PEN is effective in adults, whether it can achieve mucosal healing, whether use of PEN is crucial and whether there are any additional indications.

CDED in adults

A prospective open-label multicentre pilot trial [Yanai H, Levine A, Hirsch A, et al., to be published] aimed to evaluate the efficacy of CDED with or without PEN in adults aged 18–60 years with active mild to moderate CD for the purposes of inducing remission, maintaining remission and achieving mucosal healing. The trial design is shown in Figure 2.

Primary endpoint:

- Corticosteroid (CS)-free clinical remission at week 6

Secondary endpoints:

- CS-free remission at weeks 12 and 24

- Change in CRP and faecal calprotectin (Fcal) at week 6 and at maintenance

- Mucosal healing rate at week 24

- Tolerance and compliance

- Comparison of CDED + PEN vs CDED alone

Figure 2: Trial design

The intention-to-treat analysis found that 70% of the 40 participating patients showed a response at week 6 and 62.5% were in remission. At week 12, 55% showed sustained remission; this figure fell slightly to 52% at week 24.

Remission was maintained over time. Of those participants who were week 6 remitters (n=25, 62.5%), 88% maintained remission at week 12 and 80% did so at week 24. There were no clear predictors of week 6 remission. Inflammatory indices including CRP and Fcal reduced over time.

Fifty percent of patients achieved endoscopic remission at week 24, with a median decrease of 5 points in SES-CD. This was a 72.8% decline from the baseline. There were no severe adverse events.

The conclusion from the study was that CDED with or without PEN:

- Is effective for induction and maintenance of remission in adults with mild to moderate CD

- Improves inflammatory indices

- Improves endoscopic response and achieves endoscopic remission

- Is safe and tolerable

In addition, it was concluded that CDED + PEN may be more beneficial than CDED alone for mild to moderate CD.

Real-life use of CDED

In real life, CDED can be used in an attempt to address unmet needs encountered in some CD patients, such as those with very mild CD symptoms, with septic complications or with few other options.

Additional potential indications are CDED with advanced therapy in combination or prior to induction, as an adjunctive therapy when there is insufficient response or as a rescue strategy when there is a loss of response. It can also be a replacement for advanced therapy in patients in remission.

At our institution we have treated more than 150 patients with CDED in the last 4 years. A significant proportion of patients request a dietary approach. This proportion has increased during the pandemic due to fear of COVID-19 and the immunological impact of biologics, as well as concerns about side effects.

In a real-life cohort, remission correlated with compliance. Patients who reported being very compliant showed an 80% remission rate in phase 1, compared to 73.3% who were fairly compliant, 44.4% who were partially compliant and 0% who were not compliant.

An exploratory prospective, open label, single-arm pilot study aimed to assess clinical, biomarker and endoscopic improvement of active pouchitis in response to CDED.

Case study: CDED for pouch inflammation

An exploratory prospective, open label, single-arm pilot study aimed to assess clinical, biomarker and endoscopic improvement of active pouchitis in response to CDED.

Case study of one participant:

- Aged 44

- Female

- J pouch for UC in 2015

- Up to 30 bowel movements per day on presentation

- Response to antibiotics (multiple courses in a year) - 15 bowel movements per day (3 at night), urgency, pain

- As a result of condition, the patient lost her job and found socialising difficult

- CRP 1.3 mg/dl, Fcal 498 µg/g

- Pouchoscopy found diffuse erythema, loss of vascular pattern, ulcerations and exudate

- PDAI=8

CDED was initiated in combination with antibiotics (ciprofloxacin)

- Week 6 of CDED + ciprofloxacin

- 9–12 soft bowel movements per day, 2 per night, milder abdominal pain

- Week 12 of CDED + ciprofloxacin

- 9–12 soft bowel movements per day, 1–2 per night, no urgency or pain

- CRP 0.12 mg/dl, Fcal 250 µg/g

- Pouchoscopy found less ulceration and a normalised afferent loop

- PDAI=5, antibiotic therapy stopped

- Week 24 of CDED

- 9–12 soft bowel movements per day, 1–2 per night, no urgency or pain

Conclusions

CDED with or without PEN is effective for the induction and maintenance of remission in adults with mild to moderate CD. CDED + PEN may be more beneficial than CDED alone and its use should be encouraged in malnourished patients, those at risk of malnourishment and those with strictures or food-induced pain.

CDED can be challenging over time as it restricts food choice and may limit social interactions. However, CDED can also be empowering as patients can move between diet phases according to disease activity and social needs.

Panel’s concluding remarks

In future, indications for CDED should be defined and support programmes for patients should be further used to assist compliance. CDED should be optimised to be more sustainable, with inclusion of diverse and safe food products in each stage, personalisation of the diet according to microbiome, genetics and disease characterisation, and definition of protocols for unique situations such as stricturing disease

Important: There is a potential problem here. Who has written this piece of text? The original wording (“Prof Maharshak’s institution has treated”) suggested it is somebody other than Prof. Maharshak, whose name appears on page 4. I have assumed, however, that Prof. Maharshak is the author and amended accordingly. This decision affects the styling of subsequent headings (“Real Life Use of CDED”, “Case study: CDED for pouch inflammation” and also “Conclusions” on the next page). I have assumed that these are subheadings within Prof. Maharshak’s contribution. If they have another author, they should be level 1 headings and the author’s name should be displayed.

References

- Sandall AM, Cox SR, Lindsay JO, et al. Emulsifiers impact colonic length in mice and emulsifier restriction is feasible in people with Crohn's disease. Nutrients. 2020;12:2827.

- Naimi S, Viennois E, Gewirtz AT, Chassaing B. Direct impact of commonly used dietary emulsifiers on human gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2021;9:66.

- Singh V, Yeoh BS, Walker RE, et al. Microbiota fermentation-NLRP3 axis shapes the impact of dietary fibres on intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2019;68:1801–12.

- Levine A, Wine E, Assa A et al. Crohn's disease exclusion diet plus partial enteral nutrition induces sustained remission in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:440–50.e8.

- Logan M, Clark CM, Ijaz UZ, et al. The reduction of faecal calprotectin during exclusive enteral nutrition is lost rapidly after food re-introduction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:664–74.

- Yanai H, Goren I, Godny L, et al. Early indolent course of crohn's disease in newly diagnosed patients is not rare and possibly predictable. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1564–72.e5.

- Sigall Boneh R, Van Limbergen J, Wine E, et al. Dietary therapies induce rapid response and remission in pediatric patients with active Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:752–9.

- Levine A, El-Matary W, Van Limbergen J. A case-based approach to new directions in dietary therapy of Crohn's disease: food for thought. Nutrients. 2020;12:880.

- Sigall Boneh R, Sarbagili Shabat C, Yanai H, et al. Dietary therapy with the crohn's disease exclusion diet is a successful strategy for induction of remission in children and adults failing biological therapy. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:1205–12.