P190 Delayed IBD diagnosis leads to worse outcomes over years, with multiple implications on service delivery

Rao, A.(1)*;Bazarova, A.(2);Mitra, P.(3);Majumder, S.(4);Parigi , T.(1);Ghosh, S.(4,5);Iacucci, M.(4,5);Shivaji, U.(4,5);

(1)University Hospitals Birmingham, Gastroenterology, Birmingham, United Kingdom;(2)Institute for Biological Physics University of Cologne, Biological Physics, Cologne, Germany;(3)University of Birmingham, Biomedical Sciences, Birmingham, United Kingdom;(4)Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy- University of Birmingham, Gastroenterology, Birmingham, United Kingdom;(5)National Institute for Health Research NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre University Hospitals Birmingham, Gastroenterology, Birmingham, United Kingdom;

Background

Delays in diagnosis can be patient and health-system related. Such delays have been reported to increase overall complications in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD). The aim of our study was to report on the impact of delays on IBD-related adverse outcomes (AOs), as hospitals currently face challenges with long waiting lists in the post-COVID-19 era.

Methods

New patients referred for suspected IBD to a single tertiary care centre between Jan 2013 to Dec 2017 were identified using EMR. A cut-off time was set for each delay-type based on best average hospital waiting times. Reasons for delays until start of treatment and data on pre-defined AOs (steroid & other rescue therapies, hospitalisations, surgery) were recorded for each patient until end of June 2021. Data was analysed using multiple Pearson correlations and Cox proportional Hazard model to determine if there was a difference in survival without AOs between patients with and without delay.

Results

105 patients were identified using strict criteria (M=58; median age=32y) with a median follow-up of 55 months. The most frequent presenting complaints were abdominal pain (44, 41.9%), loose stools (40, 38.1%), bloody diarrhoea (37, 35.2%) and bleeding per-rectum (33, 31.4%). 65, 27 and 13 patients had a final diagnosis of Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and Unclassified colitis respectively, and were analysed jointly.

The longest delay-types noted: patients seeking medical attention (median=4 months; range 1 to 84 months); arranging gastroenterology clinic review after GP referral (median=5 weeks; 1 to 30 weeks); and waiting for index endoscopy (median=3 weeks; 1 to 36 weeks).

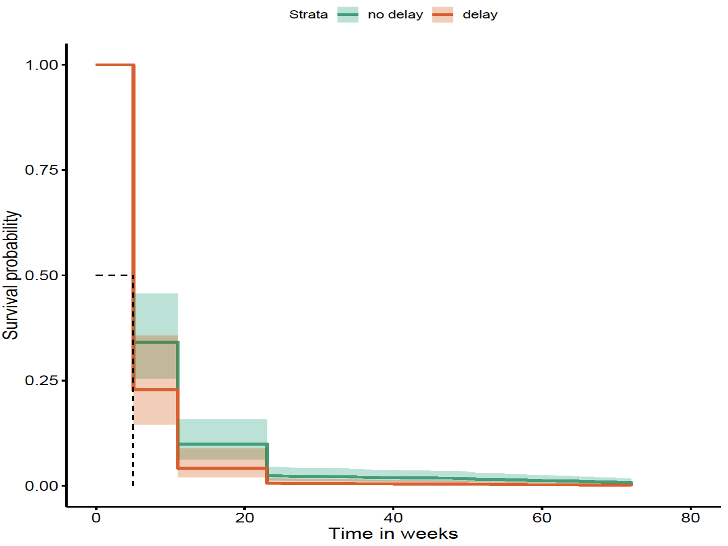

Patient stratification based on delay-type, using specific cut-off times for each showed a statistically significant difference in survival without AOs for all (when comparing delay vs no delay).

- delay in seeking medical attention (cut-off=1m; p=0.004) (Fig 1A)

- delay in GP referral to specialty review (cut-off=1w; p=0.048)

- delay in index endoscopy (cut-off=4w; p=0.01) (Fig 1B)

- delay in starting treatment (cut-off=4w; p=0.03)

Fig 1A-Time to seek medical attention (survival without AOs; p=0.004)

Fig 1B-Time from clinic review to index endoscopy (survival without AOs; p=0.01)

Conclusion

Several bottlenecks of delays increase AOs in IBD over the follow-up period. A delay as short as a week, between GP referral to specialty review, is significant in determining AOs, relevant for specialist IBD centres particularly in the post-Covid period. Endoscopy units should prioritise suspected IBD patients to reduce AOs, which is likely to have implications on service delivery and planning. Long delays observed in patients seeking medical attention highlights the need for better patient education in the community.