P375 Feasibility of the first paediatric randomised controlled pilot trial of faecal microbiota transplant for ulcerative colitis

N. PAI2, J. Popov3, E. Hartung1, L. Hill4, K. Grzywacz5, D. Godin5, L. Thabane6, C. Lee7, M. Surette2,8,9, P. Moayyedi2,8

1McMaster Paediatric FMT Research Program, 1Division of Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Department of Paediatrics- McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, 2Farncombe Family Digestive Health Research Institute, Department of Medicine- McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, 3College of Medicine and Health, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland, 4Department of Exercise Science and Sports Medicine, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 5Division de Gastroentérologie- Hépatologie et Nutrition, Département de Pédiatrie- Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada, 6Department of Health Research Methods- Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, 7Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, 8Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine- McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada, 9Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

Background

The first multicentre paediatric randomised-controlled trial (RCT) of faecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in ulcerative colitis (UC) was recently completed in Ontario and Quebec, Canada. The use of FMT in paediatric UC treatment has been limited to small, open-label case series. Unique clinical and patient factors necessitated a paediatric-specific pilot RCT. Our aim was to assess key feasibility measures of conducting an FMT trial in paediatric patients to inform design, and feasibility of larger, future multicentre studies.

Methods

Patients were randomised (1:1) to receive rectal enemas 2×/week for 6 weeks, followed by a 6-month follow-up period. Enemas contained normal saline (placebo), or RBX2660 (Rebiotix; Roseville, USA), a faecal microbiota preparation of stool from healthy adult donors (active). Patients were eligible for the open-label extension following completion or withdrawal from the placebo arm. Study feasibility was assessed through patient eligibility, recruitment, completion of sample collections, adverse events, and hospitalisations.

Results

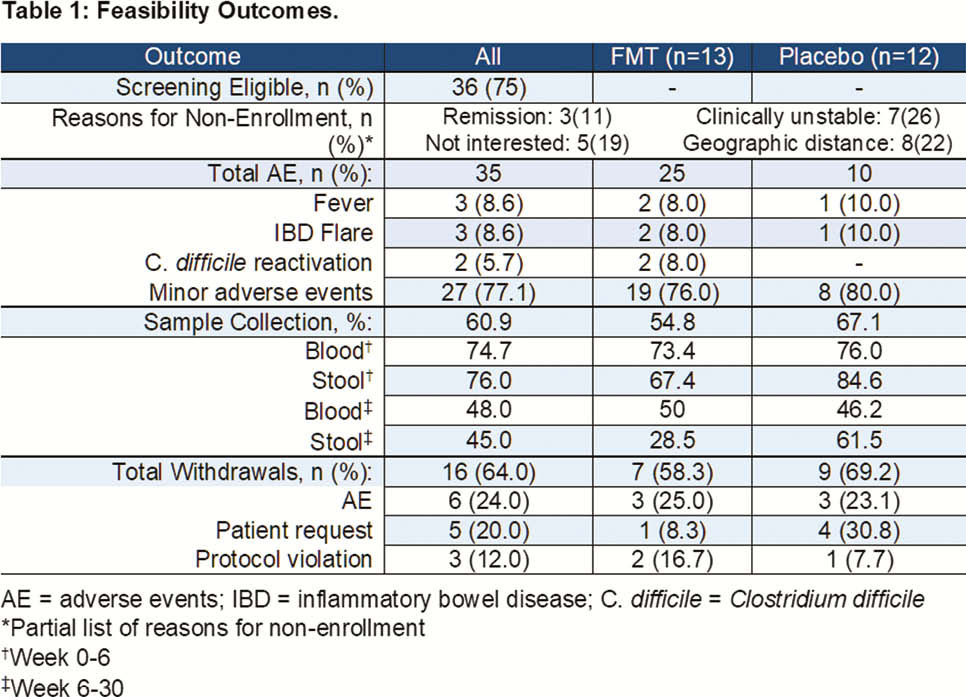

Over 36 months across two tertiary IBD clinics, 48 paediatric patients were screened for participation. 75.0% (36) met eligibility criteria for enrolment and 69.4% (25) participated in the randomised trial. 53.8% (7) of patients randomised to the placebo arm entered the open-label arm. We stratified completion of sample collections by intervention (Weeks 0–6), and follow-up phases of the trial (Weeks 6–30). 75.3% of required bloodwork was obtained during both phases; patient-provided stool samples declined from 76.0% (intervention) to 45% (follow-up). 83.0% (10) reported adverse events in the active arm, and 38.4% (5) in placebo; these were all minor and self-limited (muscle pain, cough, fatigue, etc.). No patients experienced adverse events related to enemas. Five patients experienced serious adverse events: IBD flare (2 active, 1 placebo), and reactivation of

Conclusion

In this first paediatric RCT of FMT for UC, we established important feasibility data regarding the design of FMT trials in children. Patient acceptance of FMT was high, and well-tolerated with minor, self-limited adverse events, and few serious adverse events. Return-rates of stool samples were low during follow-up; strategies to improve uptake are needed, particularly given the value of microbiome data for analyses. Overall, our study demonstrates strong interest and tolerance among paediatric patients for FMT-based trials. Future studies will build upon our protocol to enhance clinical data on the effects of microbiota-based therapeutics in children.