P414 Stoma in patiens with IBD: friend or foe? -\tEffect of stoma on course of disease, psychological well-being and working capacity

Bianchi, R.(1);Von Känel, R.(2);Roth, R.(3);Schreiner, P.(1);Rossel, J.B.(4);Barry, M.P.(4);Dora, B.(1);Kloth, P.(1);Juillerat, P.(5);Greuter, T.(6);Misselwitz, B.(5);Schoepfer, A.(6);Scharl, M.(1);Rogler, G.(1);Biedermann, L.(1);

(1)University Hospital Zurich and University of Zurich, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Zuerich, Switzerland;(2)University Hospital Zurich and University of Zurich, Department of Cunsultation Psychiatry and Psychosomatics, Zurich, Switzerland;(3)Spital Limmattal, Department of Internal Medicine, Schlieren, Switzerland;(4)Universiyt of Lausanne, Center for Primary Care and Public Health Unisanté, Lausanne, Switzerland;(5)Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Department of Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Bern, Switzerland;(6)CHUV, Department of Gastroenterology and hepatology, Lausanne, Switzerland;

Background

Knowledge on the impact of stoma formation surgery on course of disease, psychological well-being, quality of life (QoL) and working capacity in patients with IBD is scarce.

Methods

To investigate this, we analysed prospectively followed-up patients from the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort study (SIBDCS), comparing ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) with vs without stoma surgery, for both temporary and permanent stoma formation.

Results

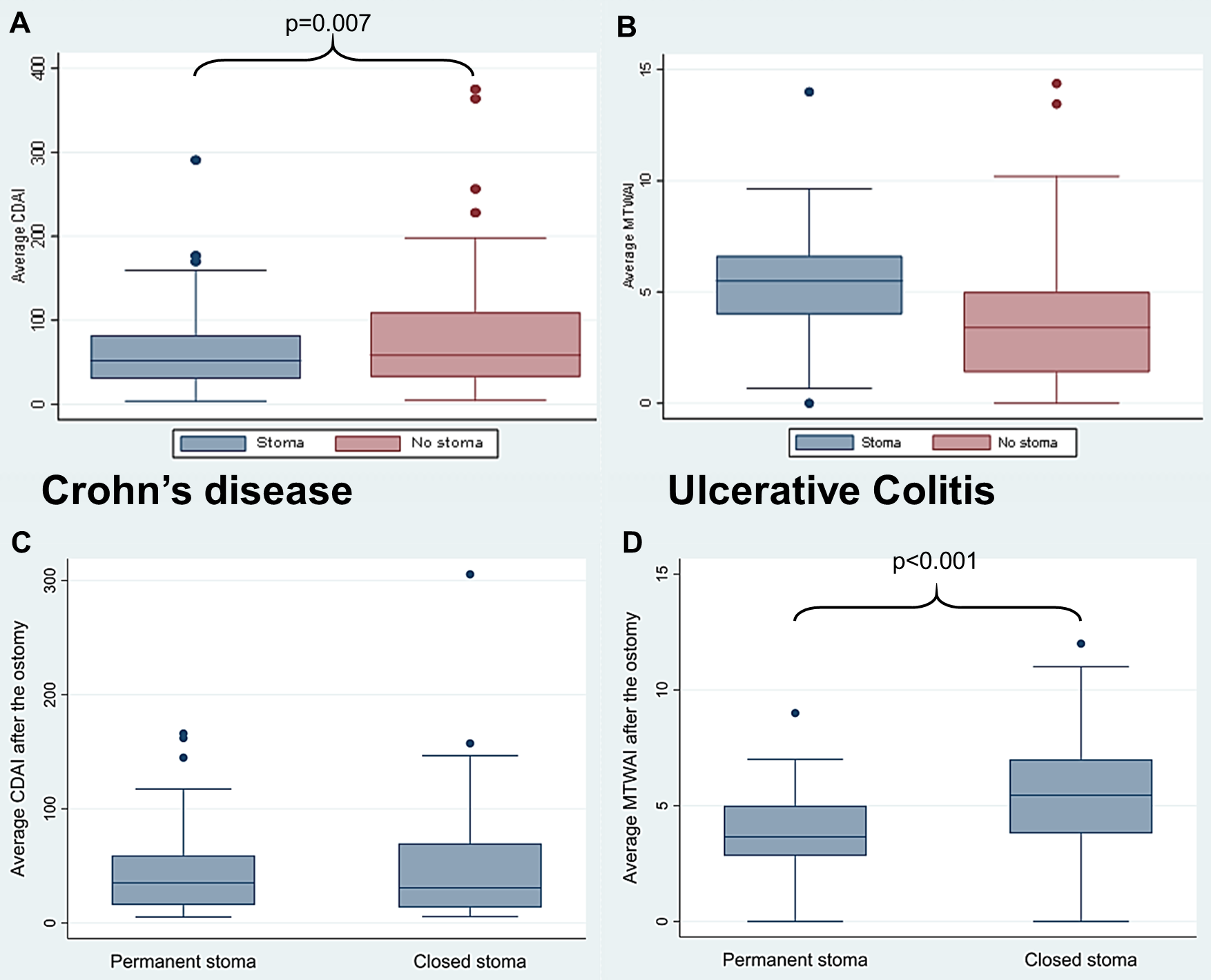

From a total of 3825 SIBDCS patients, 352 patients were included in our analysis - 176 with stoma surgery (52.8% and 47.2% with CD and UC, respectively) - amongst these 111 with permanent and 65 with temporary stoma - matched with 176 patients without stoma. Mean and maximal disease activity was lower in patients with vs. without stoma overall in CD but not in UC (Fig. 1, A/B). However, in UC, disease activity was lower in permanent vs. temporary stoma patients (Fig. 1, C/D).

Figure 1 A-D: Average disease activity with mean Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI; A) in CD and Modified Truelove & Witts activity index (MTWAI; B) and UC for patients with vs. without stoma as well as (within the stoma group) permanents vs. closed ostomy (C,D).

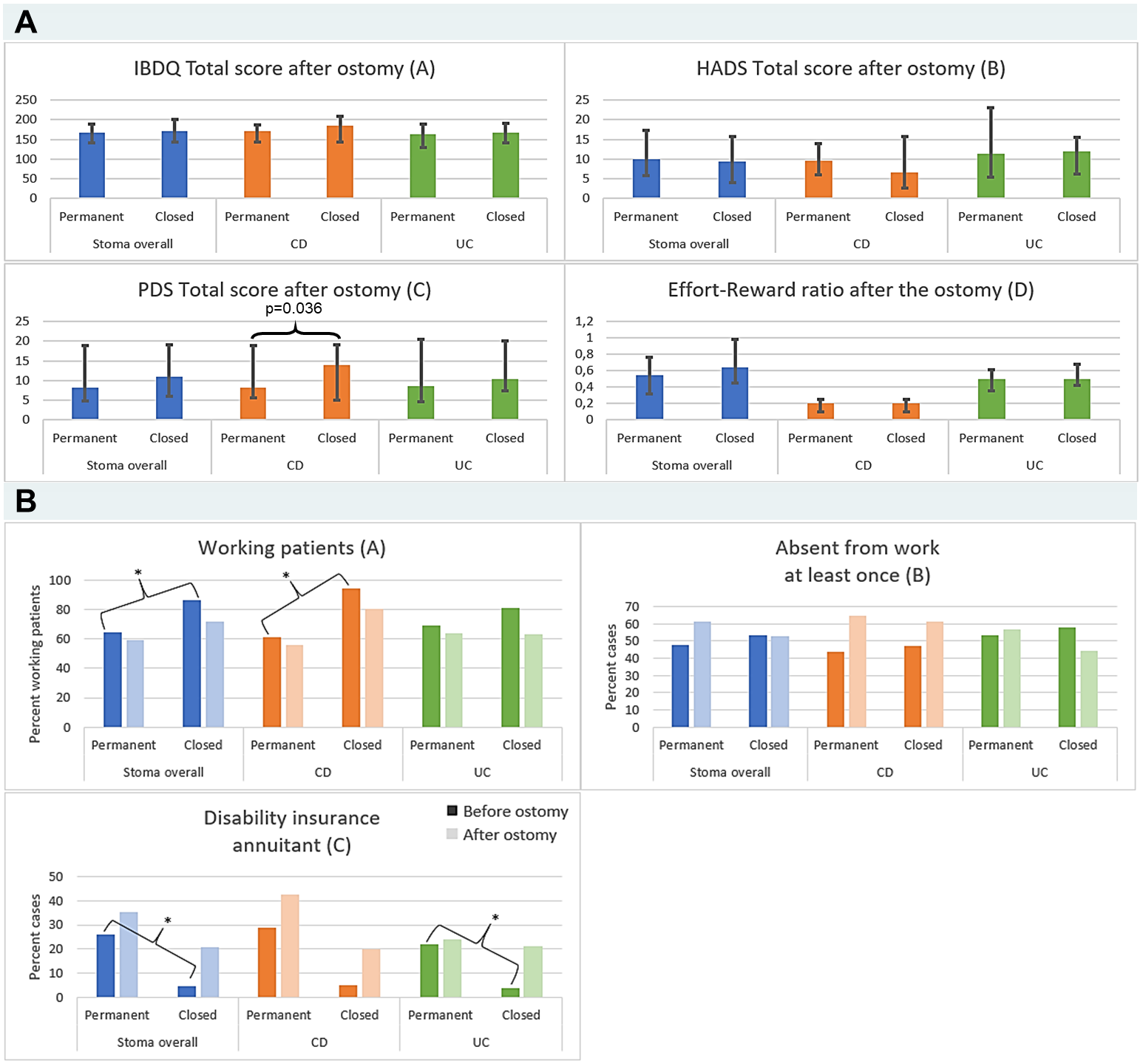

Furthermore, active EIM as well as need for steroids, immuno-modulators and biologics were lower in stoma vs. control patients. Amongst stoma patients, quality of life and psychological wellbeing was similar in permanent vs. closed stoma (Inflammatory Bowel Disease Quality of Life questionnaire Total score (IBDQ); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Total Score (HADS); Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale Total Score (PDS); and effort-reward ratio – all mean values obtained during prospective SIBDCS follow-up). However, we found a significantly lower (i.e. more favourable) PDS avoidance score in permanent vs. closed ostomy (Fig. 2A). Working capacity was lower in permanent vs. closed stoma patients (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2 A,B: IBDQ, HADS total, PDS total and Effort-Reward ratio (A), Working status, absentism from work and need for disability insurance (B) in permanent vs. closed IBD patients with stoma.

Conclusion

In CD patients with stoma surgery disease activity was significantly reduced after ostomy. Moreover, in UC we observed a benefit of patients with permanent compared to their counter-parts with temporary stoma to control disease activity. We found no differences in psychological functioning and QoL between temporary and closed stoma, with the exception of higher avoidance indicative of posttraumatic stress in the latter. In contrast, working capacity revealed to be higher closed vs. permanent ostomy.