Evolving Treatment Options for Patients with Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

This symposium was sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb

|

Presented by:

Axel Dignass, MD, PhD – Frankfurt, Germany

Iris Dotan, MD – Petah Tikva, Israel

James Lindsay, PhD, BM BCh, FRCP – London, UK

Conventional therapies remain the most common first-line treatments for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis (UC) in the EU, including aminosalicylates (5-ASAs), corticosteroids, and immunosuppresants.1 However, clinical remission is not always achieved with conventional therapies in certain patient populations.2 According to one retrospective study of patient-reported outcomes of 256 patients, more than half of patients did not achieve control of clinical measures, such as rectal bleeding or normal stool frequency, with the use of conventional therapies.2

Corticosteroids are also used for inducing remission, but there are numerous considerations for their use in managing UC, including onset of action, induction of remission, symptom control, and risks of long-term use.3,4 Despite concerns with long-term use, they are still used in many patients with UC long-term. An international survey of 1030 patients with UC and 654 physicians treating patients with UC revealed that nearly 1 in 5 patients (of the 765 patients on corticosteroids) received corticosteroids for ≥6 months within the last year.5 In addition, 43% of the 654 physicians reported using corticosteroids for ≥4 months in a typical year for patients with UC.6 Current recommendations indicate if patients fail 2 or more courses of corticosteroid therapy in the past year, or are corticosteroid dependent or refractory, then they should consider other treatment options to manage their UC.7

The treatment landscape for UC has evolved and become more focused on specific targets. Targeted therapies, including biologics (vedolizumab, adalimumab) and small molecules (tofacitinib, ozanimod), have demonstrated improvement in clinical measures—rectal bleeding scores and stool frequency scores and providing long-term clinical remission in clinical practice and clinical trials.8-15 Since the introduction of targeted treatment options, the use of biologics has increased with anti-tumor necrosis factors (anti-TNFs) currently being the most frequently used.1

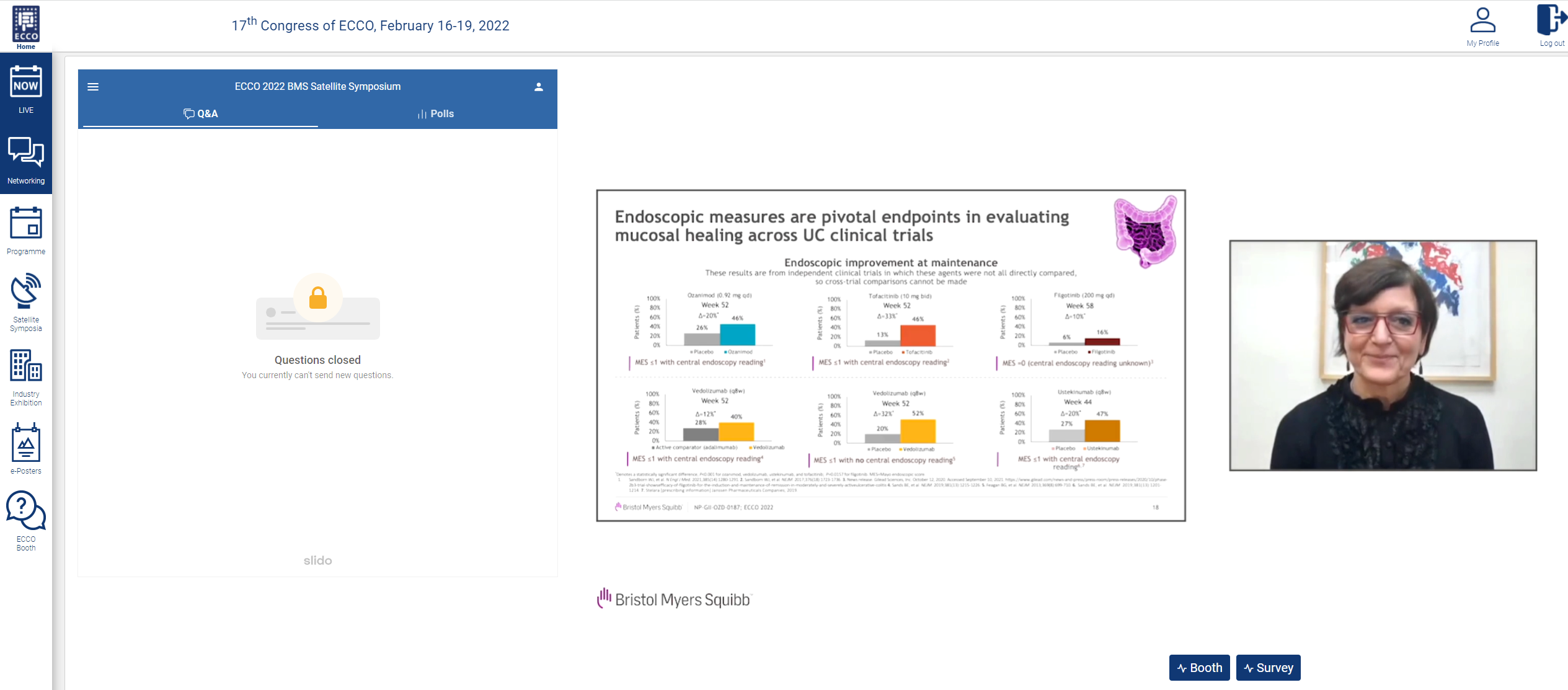

Patient clinical outcomes have been associated with improvements in endoscopic and histologic measures. Therefore, both parameters have been incorporated into international UC treatment guidelines. Endoscopy measurements are a standard practice for evaluating the mucosa to make a diagnosis, assessing disease severity and treatment efficacy, and surveilling for cancer.16 These endoscopic measures are pivotal endpoints in evaluating mucosal healing in UC across clinical trials. However, endoscopic parameters, which can be defined as the absences of friability, blood, erosions, and ulcers of the mucosa, can be subjective, and therefore can present issues in assessing clinical trial outcomes.17,18 More recent trials have incorporated central reading to help mitigate the variability in assessing endoscopic parameters. The Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) initiative recommendations have been updated to take into account the development of new biologic and small molecule treatments, as well as advancements in diagnostic technologies; the recommendations also now include histological healing as a parameter.19,20 More recently, clinical trials have also evolved the definition of mucosal healing to include histological and endoscopic measures for advanced therapies, such as filgotinib, ustekinumab, vedolizumab, and ozanimod.14,21-23

Histological remission has been correlated with improved patient outcomes. Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis from 2016, patients with UC had fewer clinical relapses (RR=0.48), less corticosteroid use (RR=0.54), and a decreased risk for colectomies (RR=0.30).24 Another prospective study revealed that histologic remission could predict reduced rates of hospitalization (OR=0.21).25 Furthermore, patients with continued mucosal inflammation at follow-up may be at more than twice the risk of developing colorectal neoplasms than patients who have minimal to no mucosal inflammation.26 Studies have indicated that histological remission is particularly associated with better patient outcomes.27 Therefore, the combined definition of mucosal healing to include both endoscopic improvement and histological remission, can be valuable in determining long-term patient outcomes.18,27-28

When choosing a treatment option, there are several clinical considerations associated with biologics and small molecules. A patient decision-making survey demonstrated that some of patients’ top concerns were related to efficacy, side effects, and ease of administration.29 Another international survey of 500 gastroenterologists also cited side effects as a barrier when considering use of biologics.30 There are many challenges associated with the initiation of advanced therapy options when treating moderate to severe UC. While patients want long-term efficacy, they may have safety concerns; thus, they are reluctant to consider advanced therapies. They may even view the need for advancing therapy as a sign of worsening disease.31-33

Targeted therapies have allowed clinicians to shift from prescribing non-specific immunomodulators toward more targeted anti-inflammatories. As more is learned about the disease pathogenesis of UC, more treatment options targeting multiple mechanisms of action have become available. The mechanism of action of small molecules in both approved and in development therapeutic options target molecules that can reduce inflammation through inhibition of internal signaling pathways or modulation of lymphocyte migration.34 Newer small molecule drugs have several advantageous characteristics, including ease of use with an oral route of administration and lack of immunogenetic concerns that may not require drug level monitoring.35-38 Overall, targeted small molecule therapies seek to address specific causes of UC to improve clinical outcomes.

More patients receiving treatment with ozanimod, tofacitinib, and filgotinib achieved clinical remission than patients who were receiving placebo at both induction and maintenance time points.14,15,23 Clinical remission was also achieved in both tumor necrosis factors (TNFi)-naive and TNFi-experienced patients with the use of ozanimod, tofacitinib, and filgotinib.9,39,40 Small molecules offer the promise of clinical remission with fewer safety concerns through more specific targeting of inflammatory mechanisms.41

Like many of the biologic therapies, small molecules have unique initiation requirements prior to starting the medication and during treatment of UC. Screening and monitoring for infections should be conducted prior to initiating therapy with ozanimod, tofacitinib, or filgotinib.39,42,43 An electrocardiogram is recommended prior to initiation with ozanimod to rule out any cardiac conditions that can increase the risk of bradycardia with S1P modulators.42 Screening for tuberculosis should be completed prior to use with filgotinib or tofacitinib.39,43 Women of childbearing age should test negative for pregnancy prior to initiation with each of the small molecules and continue to use effective contraception during treatment and after discontinuation of treatment for 3 months.42 During treatment with ozanimod, filgotinib, and tofacitinib screening and monitoring for infections and examination of skin should be conducted. In addition, live vaccinations should be avoided during therapy with all three of these drugs.39,42,43

Long-term safety data of targeted small molecules, such as ozanimod, tofacitinib, and filgotinib, can give clinicians more data and context with regard to the risk profile of each treatment option to best match each patient’s clinical presentation and concerns. Ozanimod has shown a low rate of serious adverse events that was comparable to placebo at the end of the maintenance period.14 In patients using filgotinib at 100 mg and 200 mg, the risk of serious infections, such as herpes zoster, were similar across all 3 treatment groups including placebo.23 In patients with existing risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) also receiving tofacitinib 10 mg twice a day—the higher range of the dose—VTEs have occurred.44 In February 2019, the FDA issued a boxed warning regarding VTE with high doses of tofacitinib in patients aged >50 years old with a cardiovascular risk factor.45 Looking across multiple indications in a larger patient pool, discontinuations of tofacitinib occurred in 48.2%, 13.9%, and 3.8% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis, and ulcerative colitis, respectively, in an open-label, long-term extension study.46-48 No new safety signals were seen with long-term treatment of ozanimod, and treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were at low rates in both the UC and multiple sclerosis (MS) patient populations. Severe TEAEs occurred in 10.2% and 6.1% of both UC and MS patients, respectively, exposed to ozanimod.49

With more known on the long-term safety data of these small molecules, it is helpful to consider them in the context of familiar biologic treatments. GEMINI LTS was an international, single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study of patients with moderately to severely active UC or Crohn’s disease (CD) which investigated the safety and efficacy of vedolizumab. The incidence of any adverse events or serious adverse events was 88% and 20%, respectively.50 Another analysis looked at the safety of adalimumab across multiple indications (ie, RA, psoriasis [Ps], CD, ankylosing spondylitis [AS], UC, hidradenitis suppurativa [HS], psoriatic arthritis [PsA], non-infectious uveitis [UV], non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [nr-ax-SpA], and peripheral [pSpA]) in 77 randomized, controlled, open-label, and long-term extension studies. Serious infections were the most common serious adverse events across all indications, with the highest incidences in CD, UV, RA, and UC studies.51 The concerns seen with biologic therapies, such as serious infections, are not that dissimilar from those seen with small molecules.50,51

While rare, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is also a risk with some treatment options for UC. PML is a serious opportunistic viral infection of the brain caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), typically in immunocompromised individuals, that can lead to permanent disability or death.52 Many approved drugs that target the immune response have been associated with some cases of PML. Natalizumab has been associated with the most cases of PML, with over 800 cases reported in literature and the WHO Vigibase.53 Other therapies, including methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine, all have at least 10 cases reported in the literature, whereas monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab have under 10 cases reported in the literature.

While some of these drugs used in UC have more cases of PML reported than others, it is important to note that direct comparisons should not be made with respect to case number. Many of these drugs have been available for longer periods of time or given to larger patient populations, which can presumably result in higher amounts of PML reported. Overall, the incidence of PML in many of the drugs used to treat UC remains very rare.

Small molecules and advanced therapies have demonstrated safety and efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe UC. Treatment goals have evolved to include both endoscopic improvement and histologic remission as data has emerged supporting their association with improved long-term outcomes. Long-term safety data associated with the use of small molecules and biologics can further provide healthcare professionals and patients with insights for making treatment choices that can optimize patient outcomes and ultimately lead to a better quality of life in patients with UC.

Browse through the gallery:

ECCO Faculty Q/A Session

1. Which score should be used in histological assessments? Which histologic measures are used for clinical decision making?

• Dr Dotan: The most used measures include the Geboes, Nancy and Robarts, and we use the Nancy index. Regardless of which scale is preferred, it’s important to have a common tool to understand what histological outcome is meaningful in prospective validated studies

2. What are your personal targets of mucosal healing?

• Dr Dotan Many patients can be on 5-ASAs for a long time and still not have histological remission; in such patients, we begin to implement combination therapies and gauge improvement based on prospective follow-ups

3. When you have a patient with moderate/severe UC who has failed conventional therapy and an anti-TNF treatment, how does this affect your choice of next therapy?

• Dr Dignass: I would not try another anti-TNF if they have already failed therapy. I would choose a medication with a new MOA and with a route of administration preferred by the patient

4. Given your understanding of the risks associated with JAK inhibitors, how do you counsel your patients on these risks?

• Dr Lindsay: We take into consideration any co-morbidities and patient risk factors, and collect a full blood panel to rule out any infections, while also discussing the way the drug works and what to monitor for while the patient is on the therapy

5. Do you think that the mechanism of action of ozanimod is an advantage or disadvantage?

• Dr Lindsay: The ability of this antitrafficking agent to lower lymphocyte levels without altering lymphocyte function, unlike other agents, is an advantage of the MOA. The risk of lymphopenia is due to the MOA of ozanimod, but the recent safety data across MS and UC allow gastroenterologists to better assess the impact of lymphopenia on infection rates compared to other immunomodulators

6. How do you manage the fear of zoster, since you spent some time talking about that?

• Dr Lindsay: I don’t think it’s a new issue for us, and its incidence is rare even though it occurs. Also, it is considered dose dependent with JAKi, so keeping people on the lowest dose seems to be the most appropriate strategy. Educating patients to identify symptoms and rapidly seek treatment, as well as potentially discontinuing the patient’s medication, is important

Disclaimer: This programme is not affiliated with ECCO. This symposium is intended, and should be interpreted, as an information session on scientific progress and latest developments and is not intended, in any manner, as a promotional event or any kind of inducement to prescribe or use any medicinal product(s).

References

-

Armuzzi A, DiBonaventura MD, Tarallo M, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in the United States and Europe. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0227914.

-

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Van Assche G, Sturm A, et al. Treatment satisfaction, preferences and perception gaps between patients and physicians in the ulcerative colitis CARES study: a real world-based study. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:601–607.

-

Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;11(7):769–784.

-

Tripathi K, Feuerstein JD. New developments in ulcerative colitis: latest evidence on management, treatment, and maintenance. Drugs Context. 2019;8:1–11.

-

Afzali A, Armuzzi A, Bouhnik Y, et al. Patient and physician perspectives on the management of inflammatory bowel disease: role of steroids in the context of biologic therapy. Poster presented at: 15th Congress of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO); February 12–15, 2020; Vienna, Austria. P393.

-

Rubin DT, Sninsky C, Siegmund B, et al. International perspectives on management of inflammatory bowel disease: opinion differences and similarities between patients and physicians from the IBD GAPPS survey [published online ahead of print January 29, 2021]. Inflamm Bowel Dis. doi:10.1093/ibd/izab006

-

Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68:s1–s106.

-

Hanauer S, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, et al. Rapid changes in laboratory parameters and early response to adalimumab: a pooled analysis from patients with ulcerative colitis in two clinical trials. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(9):1227–1233.

-

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D'Haens G, et al. Ozanimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1280–1291. Supplementary Appendix.

-

Hanauer S, Panaccione R, Danese S, et al. Tofacitinib induction therapy reduces symptoms within 3 days for patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(1):139–147.

-

Feagan BG, Lasch K, Lissoos T, et al. Rapid response to vedolizumab therapy in biologic naive patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(1):130–138.

-

Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(8):699–710.

-

Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):257-265.

-

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D’Haens G, et al. Ozanimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1280–1291.

-

Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1723–1736.

-

Lee JS, Kim ES, Moon W. Chronological review of endoscopic indices in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Endosc. 2019;52(2):129–136.

-

Vuitton L, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF, et al. Defining endoscopic response and remission in ulcerative colitis clinical trials: an international consensus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(6):801–813.

-

Atreya R, Neurath MF. Current and future targets for mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases. Visc Med. 2017;33:82–88.

-

Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;S0016-5085(20): 35572-35574.

-

Panés J, Feagan BG, Hussain F, Levesque BG, Travis SP. Central endoscopy reading in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2016;10(suppl 2):S542–S547.

-

Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1215–1226.

-

Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1201–1214.

-

Feagan BG, Danese S, Loftus EV Jr, et al. Filgotinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (SELECTION): a phase 2b/3 double-blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Lancet 2021;397(10292):2372-2384.

-

Park S, Abdi T, Gentry M, Laine L. Histological disease activity as a predictor of clinical relapse among patients with ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1692-1701.

-

Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut. 2015;65(3):408–414.

-

Flores BM, O’Connor A, Moss AC. Impact of mucosal inflammation on risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(6):1006–1011.

-

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ferrante M, Magro F, et al. Results from the 2nd scientific workshop of the ECCP (I): impact of mucosal healing on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5(5):477–483.

-

Antonelli E, Villanacci V, and Bassotti G. Novel oral-targeted therapies for mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(47):5322–5330.

-

Almario CV, Keller MS, Chen M, et al. Optimizing selection of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: development of an online patient decision aid using conjoint analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(1):58–71.

-

Lasch K, Liu S, Ursos L, et al. Gastroenterologists’ perceptions regarding ulcerative colitis and its management: results from a large-scale survey. Adv Ther. 2016;33:1715–1727.

-

Taft TH, Ballou S, Bedell A, et al. Psychological considerations and interventions in inflammatory bowel disease patient care. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):847–858.

-

Koliani-Pace JL, Haron AM, Zisman-Ilani Y, et al. Patients’ perceive biologics to be riskier and more dreadful than other IBD medications. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(1):141–146.

-

Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Martino S, et al. Communications between physicians and patients with ulcerative colitis: reflections and insights from a qualitative study of in office patient-physician visits. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;43:494–501.

-

Coskun M, Vermeire S, Nielsen OH. Novel targeted therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:127–142.

-

Olivera P, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Next generation of small molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2017;66:199–209.

-

Paramsothy S, Rosenstein AK, Mehandru S, et al. The current state of the art for biologic therapies and new small molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:1558–1570.

-

Shivaji UN, Nardone OM, Cannatelli R, et al. Small molecule oral targeted therapies in ulcerative colitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020.doi 10.1016/S246-1253(19)30414-5.

-

Ma C, Battat R, Dulai PS, et al. Innovations in oral therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Drugs. 2019;79:1321–1335.

-

XELJANZ [prescribing information]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc., October 2020.

-

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dotan I, Hibi T, et al. Efficacy of filgotinib in patients with ulcerative colitis by line of therapy in the phase 2b/3 SELECTION trial. Poster presented at: European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO); October 3–5, 2021; virtual. OP25.

-

Danese S, Furfaro F, Vetrano S. Targeting S1P in inflammatory bowel disease: new avenues for modulating intestinal leukocyte migration. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12 (suppl 2):S678–S686.

-

ZEPOSIA (ozanimod) [Summary of Product Characteristics]. BMS; 2021.

-

Jyseleca (filgotinib) [Summary of Product Characteristics]. Gilead Sciences; 2021.

-

Deepak P, Alayo QA, Khatiwada A, et al. Safety of tofacitinib in a real-world cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(8):1592–1601.e3.

-

Agrawal M, Kim ES, Colombel JF. JAK inhibitors safety in ulcerative colitis: practical implications. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(suppl 2):S755–S760.

-

Wollenhaupt J, Lee EB, Curtis JR, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for up to 9.5 years in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: final results of a global, open-label, long-term extension study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):89.

-

Valenzuela F, Korman NJ, Bissonnette R, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with moderate-to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: long-term safety and efficacy in an open-label extension study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(4):853–862. doi:10.1111/bjd. 16798

-

Sandborn WJ, Panés J, D'Haens GR, et al. Safety of tofacitinib for treatment of ulcerative colitis, based on 4.4 years of data from global clinical trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(8):1541–1550. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.035

-

Danese S, Wolf DC, Alekseeva O, et al. Long-term safety of ozanimod in patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) and relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) studies. Poster presented at: United European Gastroenterology (UEG); October 3–5, 2021; virtual. PO442.

-

Loftus EV Jr, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, et al. Long-term efficacy of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(4):400–411.

-

Burmester GR, Gordon KB, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Long-term safety of adalimumab in 29,967 adult patients from global clinical trials across multiple indications: an updated analysis. Adv Ther. 2020;37(1):364–380.

-

Venna N, Gonzalez RG, Camelo-Piragua SI. Case 11-2010: A 69-year-old woman with lethargy, confusion, and abnormalities on brain imaging. New Engl J Med. 2010;362:1431–1437.

-

Koralnik I. National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/progressive-multifocalleukoencephalopathy/

NP-GII-OZD-0225 03/22

Posted in ECCO News, ECCO'22, Volume 17, Issue 1